Like thrush, white line disease is a fairly simple hoof ailment that is not terribly difficult to treat, provided it’s caught early.

“White line disease is often a mixed fungal and bacterial infection, and, like thrush, it’s opportunistic,” said Dr. Bryan Fraley of Fraley Equine Podiatry at Hagyard Equine Medical Institute. “It likes to capitalize on any little defect in the hoof wall that will give these organisms a chance to get up under the hoof wall. It grows in the non-pigmented horn. White line disease affects all non-sensitive layers of the foot. The fungus involved likes to digest away keratin, which is what makes hair and fingernails, but bacteria often are isolated with it, too.

“White line disease starts at the bottom of the foot and goes up,” Fraley added. “It originates from hoof wall that was grown six months to a year ago and is now low in the foot, it slowly digests its way up. Again, it doesn’t affect sensitive tissue, just the hard keratin portion of the hoof.”

That doesn’t mean that white line disease isn’t serious, though.

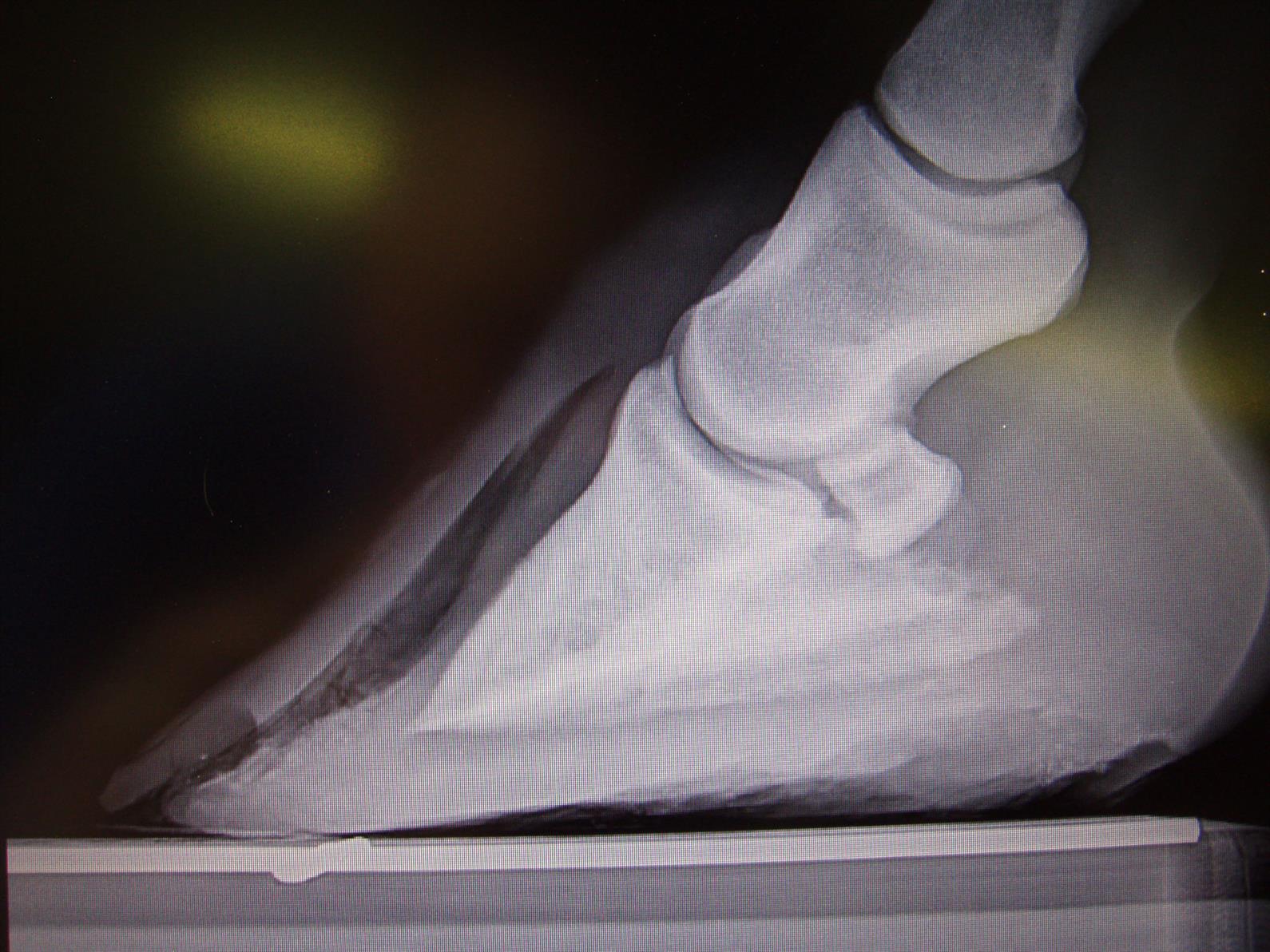

“White line disease and chronic laminitis can sometimes be confused with each other,” Fraley said. “The difference is where that cavity—a gas pocket—shows up on the X-ray. White line disease can also cause some rotation of the coffin bone, like laminitis, but it’s a little different type of rotation. Instead of the coffin bone pulling away from the laminae, it pulls away from the hoof capsule itself. So it isn’t involving sensitive tissue, but the integrity of the hoof wall is so weak that the deep flexor tendon can pull on that coffin bone and rotate it so that it looks like chronic laminitis.”

White line disease is insidious, Fraley says, because a horse with it might not show any lameness until it reaches a critical point where the coffin bone is close to rotating. At that point, the hoof can lose sole depth. “Then they can be prone to bruising or abscesses,” Fraley said, “and that can cause lameness.”

Farriers are often the first to spot white line disease, Fraley said. “They’ll notice a little cavity or void,” he explained. “Sometimes when they’re driving nails, the nail will just sink into a hole, and that’s abnormal.”

Another telltale sign: debris like straw, manure, or gravel packed up into the hoof wall, sometimes even an inch or two up in the wall.

“Sometimes a horse will abscess, and that will migrate and blow out at the coronary band, and when we investigate that we see there’s a large cavity there,” Fraley said. “Or a veterinarian might take an X-ray to examine an abscess and lameness and see the cavity on that X-ray.”

As with thrush, the key to treatment is noticing white line disease early, Fraley said.

“Don’t ignore it,” Fraley cautions. “If you ignore it, it just slowly crawls up the hoof wall. You won’t see any signs until it’s pretty severe. It can start in any defect, like a crack that originates from the ground or a simple abscess, which can give the organisms access to get in there.”

Luckily, when it’s caught in a timely manner, white line disease is easy to treat. The organisms that cause it are not particularly hardy, and many cases can be treated successfully before they ever cause serious trouble like lameness.

“If you just remove the affected hoof wall and expose the area to air, it can get better without topicals,” Fraley said.

One ally in the fight against white line disease: natural hoof clays. “If there’s a cavity--maybe it isn’t even white line disease yet—after the farrier digs out any debris or anything under the hoof wall, we’ll pack those defects with these clays,” Fraley said. “Some have bioactive honey or other things in them, and we’ll often mix copper sulfate with these clays, because that’s a pretty powerful antifungal and antibacterial. That clay can stay there pretty much through the life of the shoeing cycle in any areas that we’re worried about.

“The main thing is to recognize any little cavity or defect in the hoof wall, clean it out, and expose it to air,” Fraley said of catching white line disease. “If we see a crack that seems to be collecting debris and packing debris up into the hoof wall, we’ll sometimes open them up, make the crack wide, and expose it to air. That way, mud and debris can’t stay in the crack. It looks worse to the owner, but it might be the best thing rather than ignoring the crack. You can treat white line disease topically and try to squirt things up in there, but until you expose it to air, it’s not going to go away.”

Once the crack has been exposed to air and packed debris has been removed, your veterinarian or equine podiatrist might suggest soaking the affected hoof in a chlorine-based solution, like that used to combat thrush.

Ultimately, your best defense against white line disease may be your eyes and your ability to notice even small defects in the hoof that could serve as an open door to fungi and bacteria. And, as with thrush, if your horse’s feet are sensitive when you pick them, call the vet to arrange an examination and possibly an X-ray.

“I think annual or every-other-year X-rays are a good idea anyway,” Fraley said. “It gives you a baseline, and you pick up some of these problems like white line disease if it’s crawling up the hoof. It’s a good thing for your farrier to have, as well.”

To read part one of this two-part series, “Hoof Help: Thrush,” click here.

Want more articles like this delivered to your inbox every week? Sign up here to receive our free Equestrian Weekly newsletter.

This article is original content produced by US Equestrian and may only be shared via social media. It is not to be repurposed or used on any other website aside from usequestrian.org.